Adaptive Integration for Controlling Speed vs. Accuracy in Multi-Rigid Body Simulation

This research focuses on approaches for speeding multi-rigid body dynamics simulation of robots with intermittent contacts.

The speed of such simulations seems to be reaching a performance asymptote. Wang (2013) profiled such a simulation (using Gazebo/ODE) modeling multiple robotic scenarios and found that the bulk of running time goes to processes related to the constraint (contact, joint limit, and joint equations) solve.

This process has received considerable attention from both researchers and implementors, and large further improvements seem unlikely, at least in our area of interest (simulating typical manipulator, legged, and humanoid robots). Given that it is unlikely to reduce the computational time to take an integration step, this research seeks to find whether larger steps could be taken for simulating typical manipulator, legged, and humanoid robots.

Notions of accuracy of dynamic robotic simulations with contact

For our target application, the simulation must update at a step size smaller than the inverse of a robot’s control loop frequency (we do not wish to restrict control inputs to be smooth). Typical control loop frequencies for such robots are on the order of 1000 Hz. Such speeds yield small steps and generally low truncation error even with first order integration.

What are the practical implications when solution accuracy is not high?

The practical implications of lower differential algebraic equation (DAE) / differential complementarity problem (dCP) solution accuracy on robotics applications is an open problem, even for robots with smooth or mostly smooth dynamics.

We want the fastest simulation speed possible without artifacts

Our paper (Zapolsky and Drumwright, 2015) seeks to avoid clearly recognizable artifacts that occur with time stepping approaches: objects interpenetrating and objects passing completely through one another (tunneling). We do not currently search for transitions between sticking and slipping contact, because we believe that the effects of these transitions on solution accuracy are typically small (further experimentation is necessary to test this hypothesis).

Preventing tunneling and interpenetration

Our simulation approach uses Mirtich’s Conservative Advancement technique to prevent partial interpenetration and tunneling.

Adaptive integration technique

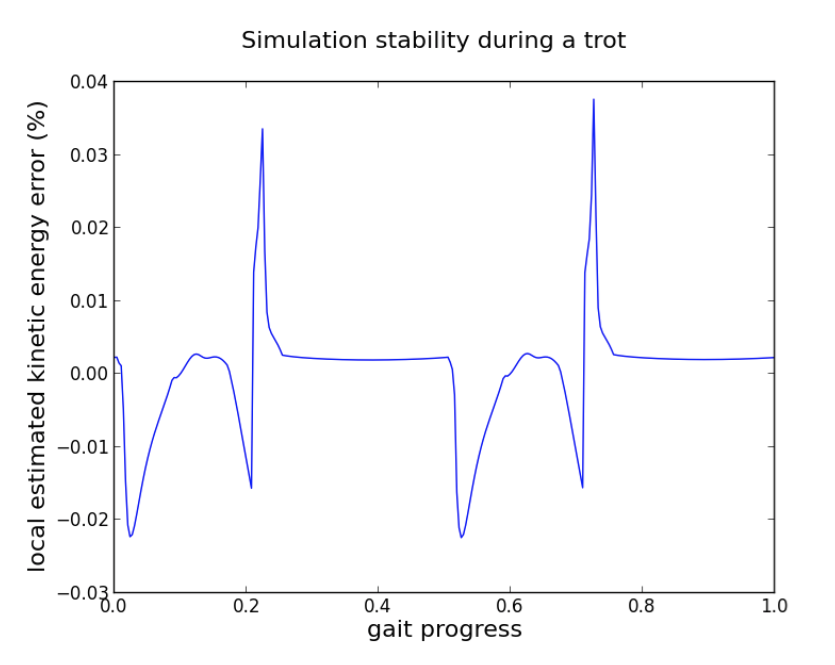

Our research uses the approach described above and standard error control techniques to integrate adaptively. If our argument (that DAE/dCP solution accuracy is less important than prevention of artifacts) is reasonable and if an interval is free of nonsmooth events, then the main inhibitor of larger steps is stability of the integration algorithm. We avoid A-stable implicit integration algorithms: they cannot be extended to prevent tunneling in straightforward fashion. We instead using an adaptive first order integrator with an estimate of the local error in kinetic energy as a proxy for system stability; the integrator takes smaller steps when necessary to keep this relative error below a threshold.

Our findings

- Local error in system kinetic energy seems to be a reasonable proxy for system stability: if the integration becomes unstable, the kinetic energy will grow exponentially over a small time interval.

- We can get 2x-3x larger step sizes for simulating a walking quadrupedal robot, but are doing 3x as much computation on each step (this can conceivably be reduced to 2x as much work using parallelism).

- An experiment with a passive dynamic walker (taken from code for Coleman et al., 2001) indicates that applying higher order integration techniques to simulating robots (modeled with rigid body dynamics and undergoing intermittent contact) is unlikely to be computationally efficient compared to current first-order approaches.

- The symplectic nature of the semi-implicit Euler integrator does not positively impact stability on non-conservative systems (i.e., most robots), compared even to the fully explicit Euler integrator.

Simulation stability (using the proxy of estimated local error in kinetic energy) during a trotting motion of the robot shown below.

Relevant Publications:

Michael J. Coleman, Mariano Garcia, Katja Mombaur, and Andy Ruina. “Prediction of stable walking for a toy that cannot stand.” Phys. Review. E, 64(2), 2001.

Jielie Wang. “Dynamic grasp analysis and profiling of Gazebo”. M.S. Thesis, Rennselaer Polytechnic Institute, 2013.

Samuel Zapolsky and Evan M. Drumwright. “Adaptive Integration for Controlling Speed vs. Accuracy in Multi-Rigid Body Simulation”. Proc. of the IEEE/RSJ Intl. Conf. on Intelligent Robots and Systems. Hamburg, 2015. [pdf]

Code and data for reproducing experiments:

All code and data for reproducing experiments can be obtained from this git repository.

Special thanks to Michael Sherman for discussion that has shaped this document.